Chain of Craters Wilderness Study Area, Cibola County

Person and place are inextricably connected. Major events in our life - whether poitive or negative - and the places where they happen are with us throughout our lives, no matter where we are. The connections between people and place transcend time and become pathways that connect us to our ancestors and future generations.

This page includes:

Language is Culture - This section shares information about what we can learn about a culture by looking at their language, even if we don’t speak that language. And it shares information about societal structure.

Profiles on Nations from New Mexico - This section provides links to profiles on each of the federally recognized tribes in New Mexico, as well as ones that used to have a significant presence here. There are also suggestions on which tribes to learn about based on County.

LANGUAGE IS CULTURE

-

Language and culture are intertwined. Language is how we share knowledge and it influences how we think and interact with others. Even if we do not speak the language, there are things we can learn about a community by looking at the language they speak. Start by looking at which tribes have similar languages.

There are nine languages and dialects spoken among the 23 federally recognized tribes in New Mexico. These languages can be grouped into four language families. The vocabulary, grammar, and structure used in each language family are completely different from one another. And, the various dialects and languages within each language group are also quite distinct, much like English and German or Spanish and French.

Tribes within the same language family often have many similarities in societal structure, religious practices, belief systems, etc. The graphic above shows the four language families represented in New Mexico (plus the language family of the Hopi).

-

Here is some basic information about terms used on the profile pages for each tribe.

Nomadic, Semi-Nomadic, or Agricultural

Nomadic and Agricultural groups both have values and behaviors that are tied to the changing seasons.

Nomadic tribes were hunter/gatherers. At times they would do raids on agricultural villages. They took advantage of Spanish horses, which helped to significantly increase their territories. This allowed for more connections to more Nations and it made them strong warriors in the fights against U.S. expansion. The Comanche, for example, practiced “leave no trace” and so it was nearly impossible for the U.S. military to track them. All of this, though, made nomadic tribes targets for U.S. military violence. The reprisal against nomadic tribes was extreme, such as making the Chiricahua and White Springs Apache prisoners of war for over two decades.

Kinship: Clans, Bands & Moieties

Kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies.

Lineage is tracing family relation to a single ancestor.

Often, families with connected lineage would form a Clan. Agricultural societies tended to have societies built on lineage and clans. Family structure and people’s roles within the family had a significant impact on their culture, values, and beliefs.

Because it was easier to travel in smaller groups, nomadic tribes had kinship that was not necessarily based on a family/blood relation. They have Bands, which is similar to extended family.

Moieties are when a society has two distinct descent groups. Or, it’s a society that has only two clans. Native Nations that speak Tewa are two-clan societies. Some call it a dual organization. This system came from their origin story.

When the Tewa people emerged from the underworld, they split into two groups: the Winter Clan, who walked along the east side of the river, and the Summer Clan, who walked along the west side. Eventually, the two clans rejoined and formed the pueblos. Each clan is associated with different ideas, similar to Yin Yang or Jung's anima and animus. Winter people are aligned with masculinity, ice, hunting, and turquoise. Summer people are aligned with femininity, the Sun, agriculture, and squash.

Winter and Summer people are mixed within each Tewa Nation. A Winter Chief rules part of the year and the Summer Chief rules the other. Some say the Summer Chief appears to be favored but that may be because the Summer season is longer.

This dual organization appears throughout the Tewa culture.

So - why is this important for healthcare?

Just like language, the society in which we are raised shapes our beliefs and attitudes. Our society defines our relationships within our community and with those outside of it. Our society is tied to our mental and spiritual health.

Understanding even these basic societal structures for the Nations in your community will help you understand how a tribe operates, what they value, how they govern, and more. Knowing a little about the tribes’ societal structures will make it easier for you to build strong relationships within those communities. And, understanding these social structures may inspire health initiatives and programs that are culturally relevant.

LANGUAGE MAPS

Language and culture are intertwined. The indigenous people of this area shared their history and knowledge through storytellers, dancers, and potters, through oral tradition and experiential learning. Without written records, if a language dies, so does the culture. The maps below show just how close the U.S. government came to succeeding in their “Termination” efforts.

Now, in this period of Self-Determination, Native Nations are prioritizing preservation of language.

MAP OF LANGUAGES SPOKEN PRE-CONTACT

MAP OF INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES CURRENTLY SPOKEN

These maps are approximations created by a linguist on Reddit.

PROFILES OF NATIONS FROM NEW MEXICO

We have compiled profiles on each of the 23 federally recognized tribes of New Mexico as well as three chapters of the Navajo Nation - Alamo, Ramah, and To’Hajiileee - because of their distinct backgrounds and unique relationships with the Navajo Nation, the State, and the Federal Government. And, because this process is about people and place - not boundaries or time - we also include several profiles about Native American communities that once had a presence in New Mexico.

Things to Consider

Look at the relationships between Nations.

Who had conflict?

Who showed mutual aid?

Who showed a change in attitudes as the world around them changed?

What variables may have contributed to their experience of colonization, such as beliefs or location?

Think about how restrictions imposed on a tribe altered their way of being.

What was the immediate result on their culture because of these restrictions?

How might these restrictions have impacted their culture, in the long-term?

Did it change their societal structure, their spiritual practice, their mode of governance?

What did they do to keep their culture alive?

Check their websites.

Do they have one? Why might a tribe not have a website?

If they do have a website, what is the focus?

Is it a resource for their community?

Is it sharing information with the general public?

Is it tied to an income source?

Does the website list services/programs or explain their priorities? How do these priorities fit within the social determinants of health?

Keep scrolling for suggested profiles based on County.

PROFILES

NOT SURE WHERE TO START?

Select your County for suggestions.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Also, read about the Piro on the Disbanded/Dosplaced/Destroyed page.

-

MAKING CONNECTIONS

If you do not already have one, you should consider creating a Tribal Engagement Strategy. Formal consultation takes place with official tribal leaders, but many requests may not require a formal consultation. There may be a Tribal-affiliated group, a Native-led organization, a specific elder, or others who may be appropriate.

Here are some things to consider before making a request:

A. NMAHC Tribal Liaison

Connect with the New Mexico Alliance of Health Councils’ Tribal Liaison, Gerilyn Antonio.

B. Know your objectives

List all the reasons you would like to connect with the Native Nations in your community. Be absolutely clear on what you want and why. For example, do you want:

To learn more about their history or culture?

To expand your partner network?

To better understand their specific blocks to accessing equitable health care?

To get feedback on your written Land Acknowledgment?

To gain consultation from Tribal Leadership?

Having clarity on your objectives will make this next step easier.

C. Have an idea of which constituents are best suited for each objective.

As with any culture, the perspective and opinions of the members of a Native Nation will vary based on their generation, gender, involvement with other cultures, etc. And, the perspective and opinion of individual members may not align with the official stance of Tribal Leadership. Connecting with the wrong demographic for a particular objective could create obstacles and connecting with the right demographic could prove to be very fruitful.

For example, if the objective is to gain perspective on the language used in your land acknowledgement, someone from a grassroots agency might be a good option because word choice is a topic they likely deal with. If you want to understand more about their history and culture, a conversation with an elder might prove to be highly insightful.

BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS

As a reminder, here is the summarized version of the goals for this land acknowledgment.

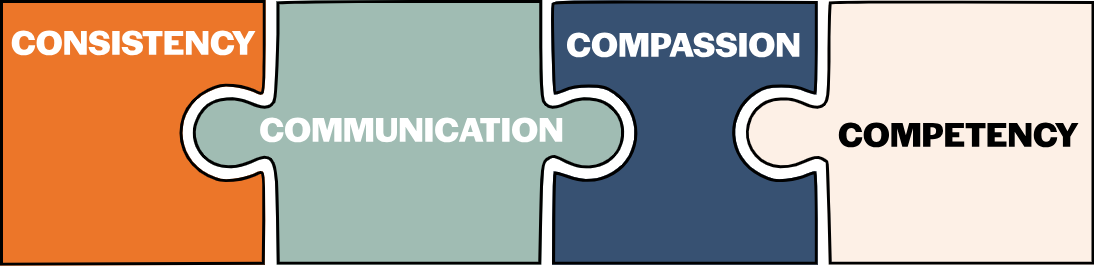

These conversations are about building relationships. It is your responsibility to prove your trustworthiness. Here are ideas on engagement that may help with building a foundation of trust.

A. Ask permission / Get approval

Get consent at every step. Even if they have given prior approval for something similar, don’t assume that transfers to a current request.

Ask if they are willing to talk and let them know what this is about.

Ask if it is okay to name their Nation or Pueblo in your Acknowledgement. If so, ask which name they would prefer and how it should be spelled and pronounced. Ask if they are willing to teach you how to pronounce it correctly.

If you want to use anything they share, make sure to get explicit permission. If your Land Acknowledgement will have several formats, then explain each format and get permission for each one.

B. Thoughtful Gifts

The practice of gift giving has unique significance in many Native cultures. For some communities, gifting was the foundation of their “economy.” Gifting is also a way of sharing resources - a necessary aspect of survival - as well as showing respect and gratitude. Gifts are often a significant part of an event or ceremony. This article shares different examples of indigenous gifting, personal stories on gifting, and other insightful thoughts.

Plan on bringing a gift. The type of gift will depend on how well you know them, where the conversation is happening, the level of engagement, etc.

Example 1: If an initial meeting takes place at their home, bring food you made to share (and leave the dish you brought it in.) Once you know them better, bring a bag of staple groceries (flour, sugar, coffee, vegetables). But don’t go over the top with a carload full of groceries, as this could be seen as an insult.

Example 2: If an initial meeting is in a public space, bring a craft you created or, something aligned with their cultural and spiritual practices, such as a bag of loose-leaf tobacco. If honoring them at an event, gift them artwork created by a member of their community.

Gifts should not replace financial compensation for significant contributions. If someone speaks at an event, give them an honorarium and/or pay for their travel and lodging. If you hire a Native business, compensate them well.

C. Elders First

If a meeting or event includes food that is not served, like a buffet or pot-luck, the order in which people get food starts with elders and moves down until the youngest eat. In some communities, children and young adults serve the elders. If you would like to “make a plate” for someone, ask them if they would like you to do that. They may refuse (because they’d rather someone who knows their preferences do it), but they will notice and appreciate the offer.

D. Actively Listen

Sometimes asking a direct question is not appropriate. Ask for stories. Ask them if it is okay for you to take notes. Remember to ask permission to use anything they share with you.

E. Stay in touch

Remember to stay in contact with them after you meet. Make a friend and be a friend. The learning process is on-going and the conversations should not end once you get the discussion you inititally requested.