Mesita Mesa and Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Santa Fe County

Current Population: 482

Language: Tewa

Early Societal Structure: Patrilineal clans with ritual patrimoieties with kivas for each moiety

Location: 11,963 acres north of Santa Fe in Santa Fe County

Click to expand

Vision Statement: Making life beautiful by bringing harmony into our lives.

Archeological studies of the area have found that the Pojoaque Pueblo area has been inhabited since as early as 500 A.D. and they had a significant population in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Pojoaque has always maintained a strong cultural identity.

Pojoaque Pueblo places an emphasis on education, because it is the best way to grow and prosper its people. They also place a high value on the preservation of its culture. For those things that have been lost or forgotten, they attempt to bring them back and further strengthen the foundation of who they are and where they have come from. They learn and adapt; accomplish and progress.

Abandoned Pueblo

In the early 1600’s, Spanish priests forced Pojoaque to build the San Francisco de Pojoaque mission. The tribe was almost reduced to starvation by the seizure of their food stores and the reduction of their ability to work their own fields. Because of the religious persecution and cultural oppression, Pojoaque participated in the Pueblo Revolt. Immediately after the Revolt, the people scattered to neighboring tribes to avoid any Spanish reprisal. When Don Diego de Vargas arrived, Pojoaque Pueblo was abandoned.

In 1706, five families returned to Pojoaque Pueblo. Six years later, the population had reached 79. An official land grant was patented by Abraham Lincoln “with the presentation of a silver cane of authority to the Governor of Pojoaque.”

Pueblo Abandoned Once More

In the 1800s, the Pueblo devasted by a smallpox epidemic They also lacked water or an arable land base for agriculture, and white settlers were encroaching. Then, around 1900, the Cacique of Pojoaque Pueblo died and the Governor left the reservation for outside employment. Once more, the residents dispersed to live at neighboring Pueblos.

They sold a 140-acre parcel of land with the sacred Mesita Mesa to Clarence Mott Woolley. He was an industrialist who worked with American Radiator and helped form the American Standard faucet company.

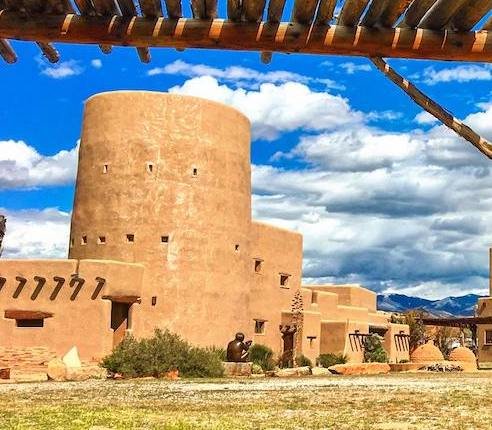

Woolley lived there for several decades. He build a polo field and worked with famed architect John Gaw Meem to design and build four homes there. His daughter worked with the noted ethnomusicologist George Herzog doing field-recordings of Pima Indian songs. One of his sons, John Carrington, served in World War II as a counter-intelligence agent and then settled in Santa Fe. The Woolley family held on to the La Mesita Ranch until 1959. The property fell into disrepair, with squatters living in the Meem buildings. In the 1980s, La Mesita Ranch was purchased by a wealthy equestrian who fully renovated the property and buildings and added world class indoor and outdoor equestrian facilities.

The People Return….To Stay

An act of Congress in 1933 caused the Bureau of Indian Affairs to publish ads in local newspapers asking for Pojoaque tribal members to return or face complete loss of their heritage and land. Fourteen people returned (from the Tapia, Villarial, Romero, and Gutierez/Montoya families). They were awarded land grants in the Pueblo land base. In 1936, Pojoaque Pueblo’s 236 members became recognzied by the United States. At the time, they had a total of 11,963 acres.

In the 1990s, Pojoaque opened Cities of Gold Casino. In 2008, they opened Buffalo Thunder Resort & Casino and they bought back La Mesita Ranch. They turned La Mesita into a luxury estate that was available for destination weddings. The Meem homes housed an extensive Native American art collection. La Mesita closed following the pandemic.

The Pueblo put the 142 acre property on the market in June 2023 for a mere $7.3 million.

Mother Village

In one account of Tewa origins, all of the known Tewa people dispersed to their present villages from Pojoaque, making Pojoaque, the “mother” village for all of the historic Tewa people. The ancestors of the Pojoaque people likely migrated into the general vicinity of the present Pueblo from the Four Corners region late in the first millennium A.D. Their Anasazi ancestors built and occupied some of the cliff dwellings of the Mesa Verde area, and one or more of the large villages of the Montezuma Valley in southwestern Colorado.

Pojoaque Pueblo places high value on the preservation of its culture. It is continuing to regenerate the Native American culture of New Mexico by using its gaming revenues to construct the Poeh Cultural Center. Pojoaque Pueblo is also taking an active role in training promising Native American artists. By teaching artists, the Pueblo feels it can promote Native American Art in the international world.

Pojoaque youth attend either the public schools in Pojoaque, the Santa Fe Indian School, or the San Ildefonso Day School.

Pojoaque Pueblo has used some of its revenues from gaming to donate money to the Pojoaque Valley School District. The funds donated by Pojoaque Pueblo are being utilized for travel to academic and athletic activities. The emphasis on education is significant to Pojoaque Pueblo because it is the best way to grow and prosper its people.

When the Pojoaque Valley Public School’s water storage system broke down, leaving the school without water for several days, Pojoaque Pueblo donated the money to repair it.

Preserving Culture

In 1988, the Pueblo of Pojoaque established the Poeh Cultural Center as the first permanent tribally owned and operated mechanism for cultural preservation and revitalization within the Pueblo communities of the northern Rio Grande Valley.

As stated on the Poeh website:

Old rhythms of life and ways of making beauty are still vital. People bring beauty to the world on a pathway of being, doing, and sharing called the Poeh. In the Tewa Pueblo language, Poeh translates to “path,” and the Poeh Cultural Center embodies that pathway, the essence of what it means to be a Tewa person – to be Pueblo.

The Poeh has become a resource for Pueblo people to learn the arts and culture of their ancestors. The facility resembles a traditional Pueblo village with its adjacent art studio buildings and outdoor gathering areas. The Center emphasizes the arts and cultures of all Pueblo People, focusing on the Tewa-speaking Pueblos of Pojoaque, San Ildefonso, San Juan, Santa Clara, Tesuque, and Nambe.

The Poeh mission is to be a gathering place for the respectful sustaining of Tewa traditions through being, doing and sharing. The objectives from that mission include:

Being – Acknowledging the respectful awareness of the place, people and circumstances is necessary to being in harmony. Being is the process, the manner in which anything is done.

Doing – Teaching that life and creativity are inseparable. Doing is part of the life path, the creating and expressing of one’s soul is essential to harmony within one’s social context.

Sharing – Living people find meaning in relationships between themselves and others. Reciprocal love and caring are important, as each person becomes a part of the whole.

The Poeh Advisory Committee is made up of representatives from the Pueblos of Pojoaque, Nambe, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Tesuque, and Ohkay Owingeh.